A colleague sent me a video of birds flocking yesterday. He was excited by the implications for self-organizing in human systems, asking what are the leadership mechanisms behind flocking?

Since finishing Engaging Emergence: Turning Upheaval into Opportunity, I’ve been thinking a lot about the nature of leadership in networks. Social networks have some parallels to flocks.

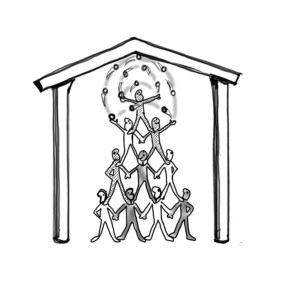

Think about the difference between pack animals, with alpha leaders keeping others in line versus birds, ants, bees, or other animals that seem to function with no one in charge. These interactions call on different leadership skills than rising to the top of a pyramid.

What can we learn from flocks, swarms, hives, and other leader-full forms of organizing? More, how can human consciousness enhance the effectiveness of these collective forms of leadership? We live in an age in which networks are an emerging means for organizing. They are more responsive, resilient, creative, and let’s face it, more fun than most hierarchical organizations I’ve experienced. Over time, hierarchies may well give way to networks as our dominant organizational form. Understanding new leadership skills will help us transition.

I’ve observed that leadership in social networks is a more multi-threaded phenomenon than hierarchical leadership. For example, traditionally, we rely on a few people to make strategic decisions for everyone else. Increasing complexity – a more diverse public, greater access to a broader range of perspectives, technological innovations affecting scale and scope of just about everything – makes this strategy less effective. No longer can a few people with relatively similar backgrounds and perspectives make the best choices for a whole system. Whether companies, communities, or social systems, like health care or education, networks call forth new approaches to decision making and leadership.

The Nature of Networks

Social networks are loosely connected, brought together largely by common purpose and personal passion. Following the boss’ orders just doesn’t work in networks. So how does anything get done? More basic, how do people know what needs doing?

Leadership in networks is relational, collective, and emergent. As I’ve read more about networks, two dynamics rise to the top when thinking about how they function:

- hubs form and evolve; and

- links connect.

How do these dynamics play out in social networks? My experience with network leadership has been influenced by a seminal experience with the Spirited Work learning community. Spirited Work met for an extended weekend four times a year over seven years. We met in Open Space, a process that supports groups in self-organizing around what matters to them. After the first couple years, the four founders did something quite unique: they stepped down as the sole leaders and invited anyone who felt called to do so to step in to steward the community. In other words, leadership became self-selected. It seemed such a great learning laboratory that I stepped in.

We, the stewards, became a hub for the Spirited Work community. We discovered that whatever challenges existed in the larger system showed up in our meetings. Stewarding was the intensive course! As we brought our diverse perspectives and interests together, we learned to listen for what was beneath the dissonance of our differences because it contained the seeds of breakthrough.

For example, early in our life, we had a financial crisis, discovering our income wasn’t covering our costs. A philosophic clash arose between paying our bills and welcoming whoever wished to participate regardless of their financial means. The larger purpose of Spirited Work – learning to link spirit to practical action on behalf of the community and the world – held us together as we worked through our differences. Ultimately, someone suggested holding an auction to raise funds. A few people took on the task and at our next gathering, the auction debuted. Not only did we clear half our debt in that first auction, people had so much fun sharing their gifts on behalf of the community, it became a regular activity. And our financial woes were permanently resolved.

Leadership and Network Hubs

From the outside, hubs in a network look a lot like hierarchical organizations. They are groups of people organized to accomplish something together. That makes it easy to confuse leadership of a hub with hierarchical leadership, thinking the same rules apply. Not! Giving orders, chain of command, top-down decision making doesn’t function when people choose whether to participate.

Hubs form because people are attracted to them. Hubs grow when people are drawn to the purpose and/or the people and believe that they can both give and/or receive something of value. The remarkable communities that maintain the Wikipedia or fill the Open Source software movement are examples of networks producing real-world benefit.

Leadership and Network Links

Link leadership is elusive because it doesn’t fit our traditional thinking about leadership. Why is connecting people or organizations a form of leadership? If you want breakthroughs, interactions among those who don’t usually meet is an essential ingredient. And when hubs connect to hubs, ideas can spread like wildfire.

While sometimes those connections are random, as often, they’re the work of people with a knack. Malcolm Gladwell famously identified three types of link leadership in his best seller The Tipping Point: How Little Things Can Make a Big Difference. He called them connectors, mavens, and salesmen.

Hubs and links attract different personality types. As someone who tends to be part of stewarding a hub, I have developed a complex relationship with linkers. They come late to meetings (if they show up at all). They often bring dissonant ideas from “out there”. They never really seem to fully belong to the hub. So they’re easy to discount. And doing so is always unfortunate. And I’ve discovered, they often feel unappreciated.

I’m learning to love linkers! They are late or seem outside because they spend their time with those at the margins. They are often the source of new ideas or differences that can attract others who, in the abstract are desirable, but aren’t getting involved. Skilled linkers learn how to bring outside perspectives and participants in graciously.

There’s So Much More To Say!

I could keep writing because there’s so much more to say. And even more to learn. Still, I’ll stop for now, knowing my understanding of the multiple skills and aspects of leadership in networks will continue to evolve.