Life is either a daring adventure or nothing.

—Helen Keller, The Open Door

We have prepared ourselves to engage and equipped ourselves to host, with a clear purpose and spirit of welcome. We have invited a diverse group to come together. We are poised to step in, confident that productive outcomes are possible.

How do we engage so that we achieve the best possible outcomes?

This chapter covers practices at the heart of engaging emergence: inquiring appreciatively, opening, and reflecting. In addition to descriptions, stories, and tips on these practices, I offer two practices that support reflecting: naming and harvesting.

Inquire Appreciatively: Ask Bold Questions of Possibility

How do we inspire explorations that lead to positive action?

If your first impulse when facing disaster is to ask questions that surface images of a positive future, your chances of making it through upheaval increase. It kept psychiatrist Viktor Frankl alive, as he continually sought meaning even in a concentration camp during the Holocaust.1

Ambitious, possibility-oriented questions are attractors. They bring together diverse people who care. They disrupt, but do so by focusing on opportunities for something better, more meaningful. They help to create a welcoming environment, opening the way to discover what wants to emerge. A useful general question is “Given all that has happened, what is possible now?”

This question acknowledges the present situation without making it bad or wrong. And it focuses on the future, setting the stage for a productive inquiry. If we don’t know the answer and are genuinely curious, we’ve got the beginnings of a great question. Here’s a question about great questions: “How do we shape inquiries so compelling that they focus us on the best of what we can imagine, attract others, and connect us to realize what we most desire?”

Bold, affirmative questions bridge chaos and creativity. They mobilize change by helping us to envision our dreams and aspirations. Such positive images generate positive actions. Appreciative inquiries attract people from different aspects of a system to get involved. Tensions and conflict surface creatively when we bring together those who care to explore positive possibilities.

One creative idea that arose from Journalism That Matters is possibility journalism. In a sense, it codifies possibility as a journalistic principle. Think of it as a sixth W added to journalism’s traditional who, what, when, where, why, and how. The sixth W: What’s possible now?

Common Language Project cofounder and reporter Sarah Stuteville provides an example:

I was working on a story in little Pakistan in Brooklyn, hearing about the experience of families of who had members deported, mostly young men. I was talking to that community and to the non-Pakistani community. People felt strongly on different sides of the same issues. This was the first time that I asked, “What’s possible now?” It may have come out of frustration, as it is hard to have conversations and not get anywhere. I threw my hands up and said, “OK, what is your ideal solution?” And everything changed. My contact began speaking of what coming to the U.S. had meant to Pakistanis prior to 9/11 and what he hoped it would someday be again.

Her partner Jessica Partnow offered a second story:

We—Sarah and I—were in the Middle East, talking with a Palestinian about frustrating, polarizing material. He kept repeating the same ideas over and over. So we asked that magic question: “Given what’s happening, what’s possible now?” It shifted the interview completely, as our contact began envisioning the situation in a completely new way, sharing his commitment to live a life with meaning in spite of the dangers.

As the Common Language Project people discovered, possibility-oriented questions don’t avoid the pain of current reality; they help us to face it. The stories we tell ourselves shape the way we see the world. And that shapes our behavior. Asking “What’s possible now?” follows life energy toward hopes and aspirations. While not denying harsh realities, it shifts a story’s center of gravity from hopelessness and despair to possibility for a better future.

Great questions help us to face what we resist, creating room to be curious, to engage, contribute, and learn. Unapologetically affirmative inquiries orient us so that we can face the unknown with a strong spirit.

Picture the scene: Systems are failing, and people in traditional leadership roles are stumped. Discord fills the air. What has worked in the past no longer functions. Even if traditional leaders believe they are responsible for the rest of us, given the complexity of today’s world, they have no chance of having all the answers. Leaders are set up for failure when ordinary people expect them to solve all the problems. Leaders who expect themselves to do so shoulder an impossible burden.

In truth, we’ve been acculturated to this trap, trained by school systems that set the expectation that we are supposed to know the answers. No wonder we resist complex situations in which we could not possibly, particularly on our own, have the answers!

Yet, when we face intractable issues, ultimately a turning point comes. We often experience that moment as a crisis and acknowledge that we do not know what to do. While it may initially feel like defeat, this moment is both terrifying and liberating. Into the chaos of not knowing, asking a question that invites others to join together in a search for answers provides a light in the darkness.

Bold, affirmative questions help us enter into mystery. They create some sense of safety. The unknown becomes a source of creativity where together we just might find some answers. When we reach the edge of known territory, ready to enter the unknown, a powerful inquiry orients us for the adventure ahead. It creates a safe haven so that when we step into terrain with angst or fear or despair or upheaval, we enter with our dreams and curiosity intact. We are able to stay in the fire to face whatever arises. We have paved the way for making the most of our differences by engaging disruption creatively.

Tips for Inquiring Appreciatively

Inquiring appreciatively is a life-changing skill. It helps us to find possibilities in any situation, no matter how challenging.

Develop the art of the question. Practice asking questions that focus on possibilities. Here are some characteristics of great questions:

• They open us to possibilities.

• They are bold yet focused.

• They are attractive: diverse people can find themselves in them.

• They appeal to our head and our heart.

• They serve the individual and the collective.

Some examples:

• What question, if answered, would make a difference in this situation?

• What can we do together that none of us could do alone?

• What could this team also be?

• What is most important?

• Given what has happened, what is possible now?

Ask questions that increase clarity. Positive images move us toward positive actions. Questions that help us to envision what we want help us to realize it.

Practice turning deficit into possibility. In most ordinary conversation, people focus on what they can’t do, what the problems are, what isn’t possible. Such conversations provide an endless source for practicing the art of the question. When someone says, “The problem is x,” ask, “What would it look like if it were working?” If someone says, “I can’t do that,” ask, “What would you like to do?”

Recruit others to practice with you. You can have more fun and help each other grow into the habit of asking possibility-oriented questions. But watch out: it can be contagious. You might attract a crowd.

Appreciative questions provide a safe haven in which to explore disruptions, to open to the unknown.

Open: Be Receptive

How do we release assumptions of how things are to make space for new possibilities?

Opening happens in an instant. It is that moment when we let go of the beliefs that give our world order, and everything changes. We enter the heart of emergence. When Harry Potter stepped on the train platform to Hogwarts, he entered a world where the people in paintings talked and staircases moved at random.

While our situation may not be as radical as Harry’s, opening sets us up for adventure. We no longer know what signals best organize our decisions and actions. Now is the time when all that pre-work—embracing mystery, choosing possibility, clarifying intentions, and so forth—pays dividends. We may not know the principles that organize our world, but at least we’ve prepared to face the unknown.

Ironically, “being open,” “letting go,” and “being receptive” are often judged as passive qualities. In practice, what could be more courageous than stepping in, with all of the energies—dissonant and resonant—that appear when difference is truly welcomed? Letting go of assumptions that have served us well is challenging. Yet without doing so, creativity has no space to flourish.

Facing significant change involves radically different beliefs and skills than handling daily routines. The landscape is filled with such uncertainty that virtually every effective action is counterintuitive. For example, consider doing business in an unfamiliar culture. Perhaps I look someone in the eye to communicate appreciation. Coming from a culture in which direct eye contact is inappropriate, the person interprets my look as aggression. We’re off to a challenging start!

So set aside current assumptions. Be willing to say, “I don’t know” and “We’re making it up as we go along.” These are today’s forms of courage and strength. Stand on the shore of the known world and step into the creative waters of the unknown. It takes both exuberance and mindfulness. Pioneers thrive in this territory, exploring the differences, passions, perspectives, ideas, and dreams among us that make for creative engagement.

We open up once our intentions are clear. It makes sense. Why would we be willing to embrace disturbance without the promise of creative and innovative answers on the other side?

What do we want to accomplish? Is it a thriving organization or family? Or perhaps we envision a community that cares for itself. Whatever the focus, being receptive to disturbance is tough when we have been trained to just do something. We discover that finding our way is not a solo act. It demands more than “input.” Wholeheartedly (and whole-mindedly) involve people from the many aspects of a system touched by disturbance.

Ironically, once we join others in the waters of difference, most of us find it exhilarating. We are freed from the “way things are,” and creativity surfaces in abundance. Challenge and opportunity abound. Together, we revisit old ground with the benefit of each other’s perceptions. We discover new and common ground. Engaging emergence can take on an almost mystical quality as chance interactions lead to unpredictable breakthroughs.

I had a challenging opportunity to open to the unknown when asked to host an Open Space Technology meeting for 1,800 street kids and 300 teachers in Bogotá, Colombia. It tested my faith in myself, in the Open Space community of practice, and in the Open Space process itself. It reminded me that opening, being receptive to what’s present, involves risk. It takes a leap of faith. I am glad I made the leap.

I was going to Bogotá to teach a class. One of my contacts, Andrés Agudelo, invited me to work with him on a two-day Open Space meeting for 2,100 people. It was with a Catholic organization that prepares street kids, ages 14–22, for jobs. Only one Open Space meeting larger than 1,000 had ever been done. Still, I said yes.

When I arrived in Bogotá, we visited the site for the conference. It gave me reason to question my sanity. The room was designed to hold 1,000 people. As we considered alternatives, we realized that the courtyard leading to the room could accommodate 2,100. But we were in the rainy season. That’s when I took the leap. I thought to myself, “I’m working with a religious organization. We’re in God’s hands.”

The challenges continued. The organization received word that employers who provided jobs to the training program were threatening to quit. They said that kids were getting stoned and were stealing. The theme for our meeting took on a fear-based twist: from finding the best possible job opportunities, it became saving the jobs they had.

The oddest part is that I never panicked. Rain seemed inevitable, and 2,000 people would not fit in the room. The theme was the most fearful I have ever worked with. And one other item: I don’t speak Spanish. Yet I was calm. I just knew it would work. Perhaps it was because I had a great partner in Andrés. And we were working with people who had handled huge crowds before. While they needed my expertise on Open Space, the kids, Andrés, and I were in good hands in every other way.

The day of the event dawned with blues skies and sunshine. I consider it a miracle. We convened in the courtyard. The event was spectacular, with two days of lively conversations that led to breakthroughs for the kids and their teachers.

Perhaps my calmness was due to the Open Space community of practice. Since 1996, its listserv has provided stories and advice for opening space. It gave me the confidence to do this work. I felt like I had a huge virtual consulting firm at my back. And for that I am deeply, deeply grateful.

When the unknowns are overwhelming but the rewards seem worth the risk, opening releases us into an adventure. Some of the most exhilarating and satisfying moments of our lives occur because we take that leap of faith. Such is the best of emergence.

Tips for Opening

Opening takes only a moment, but it may be the most courageous practice for engaging emergence.

Be clear about intentions. Openness requires boundaries. Intentions clarify focus and set direction. Clarity of purpose creates boundaries that guide us from the inside out.

Do your homework; let go of the rest. Identify what matters and handle it. How we work with a crisis is a great teacher: we quickly discern what is critical and release everything else.

Trust yourself. We can study, prepare, and practice forever. Ultimately, safety, confidence, and the ability to rise to the occasion come from within. Decide what you need, handle it, and step in.

Go with friends. Challenges are best met with a diverse company of friends. Among you are more eyes, ears, hands, skills, and knowledge to respond. It is also more fun.

When we open to engaging, the practice of taking responsibility for what we love as an act of service moves into full swing. Whatever specific work we do, what matters to us is our guide. We’re in the heart of creative engagement, discovering the differences that make a difference. While stumbling over disturbances, listening to ourselves and others, teasing out distinctions, connecting with what attracts us, and experimenting along the way, we ultimately notice what is coalescing. Reflecting helps us find our way to coherence on the other side of the chaos.

Reflect: Sense Patterns, Be a Mirror

What is arising now?

Reflecting helps meaning to coalesce. It is listening’s mirror, making visible what we sense. It supports us in stepping out of the flow of activity. And it helps us to notice the larger patterns taking shape among us. By reflecting, we test whether we are ready to come together. Asking reflective questions helps us to perceive what is converging. What are we learning? What surprised us? What is meaningful? What “simple rules”—patterns, assumptions, principles—are surfacing? What can now be named? Buddhists say that you cannot predict enlightenment, but practicing meditation prepares the way. As both a solo and collective act, reflecting prepares us to notice what is shifting even as we experience it.

I use two complementary definitions for reflecting. They both help meaning to coalesce. The paragraph above describes reflection as contemplation, sensing patterns arising. This form of reflection involves actively seeking coherence. Reflection also means to be a mirror for others—to repeat their words or describe their feelings.

In this second form, reflecting is listening going deep, being a witness for another. Reflecting back the words and feelings of speakers helps them to hear themselves. It can get underneath ineffective expressions—shouting, whining, bullying—to the deeper longings buried in their angst. Supporting others to hear themselves clarifies the heart of their cry. Perhaps it helps them to realize what they wanted to express for the first time. Feeling fully heard frees them to listen to others.

Both forms of reflecting help us to notice our differences and stay connected. We discover the larger, more complex picture painted by our diverse views. That bigger picture is often an unexpected, coherent pattern that could not have arisen without deep expressions at the heart of our differences.

Reflection prepares the way for a new, wiser, higher-order coherence to emerge. What seems a contradiction—expressing individual desires when collective action is needed—is a pathway for coming together. My colleague DeAnna Martin offers a story of reflecting using Dynamic Facilitation, a process that helps individuals, groups, and large systems to address difficult, messy, or impossible-seeming issues. It does this by stimulating a heartfelt creative quality of thinking called choice-creating, where people seek win-win breakthroughs. (See “About Emergent Change Processes” for a description of the Dynamic Facilitation process.)

In the story, the power of reflecting comes through as participants engage their creativity, discover what they really want, and uncover possibilities they can pursue. The magic of solutions emerging when least expected is a highlight of DeAnna’s story.

I facilitated a nine-member countywide parks and recreation volunteer advisory board that faced a familiar dilemma: increasing demand for services and decreasing sources of revenue. Among the board were a business owner, Little League coach, park volunteer, criminal justice system employee, retired professor, land developer, nonprofit director, community advocate, and mom. Also present was the board’s staff-support person. They came from disparate cities—from the well-funded, liberal tourist destination to the poor, conservative rural town.

They began by looking at the complexity of their situation. What was the annual budget? Where did it come from? What were the annual expenses? Who cared about this? What did other agencies do about this issue? Two clear solutions emerged:

1. Like libraries, form a “junior taxing district,” requiring voter approval; or

2. Acknowledge the cuts in revenue and cut back services.

A clear division surfaced over these options. Still, the participants shared a sense of despair and sadness in losing what all of them loved. I reflected—mirrored back—to them their proposed solutions and these feelings. In the process, I welcomed the dissonant voices, more like whines: “Passing a levy is too much work.” “We don’t even know what the people want.”

With each reflection, the solutions and the issue evolved. The problem became, “How do we engage the public in figuring out what they want?” A new solution emerged:

3. Use fear to motivate the public. Put “We will be closing our most-loved park unless we can get more funding” on the front page of the local newspaper.

This solution wasn’t quite right, either. What if no one cared about a park closing? The solution evolved yet again:

4. Put something in the newspaper and get the public’s opinions about the proposed solutions: forming a junior taxing district or cutting programs.

Dynamic Facilitation helps groups to arrive at shared, unanimous outcomes. Three hours and 45 minutes into this four-hour meeting, the group appeared to know how it would proceed. A moment of silence invited a board member to speak: “If we vote to approve this plan, I cannot be on board. I care about our parks too much. I couldn’t threaten to close one of them or do that to those who love them and use them as much as I do.”

In my old facilitator mindset, with five minutes left, I would have ended there. Instead, I invited possibility. I asked, “Given that, what else might this group do?”

Someone spoke up: “We need to be united in moving forward. I want to find a better idea.” Another board member hopped up and down in his seat. He had a novel approach:

5. We host meetings with potential partners like school districts, criminal justice agencies, sports leagues, youth programs, senior centers, and local elected officials. We share our situation and invite them to create partnership agreements to share the costs. We also host public meetings to share our situation and invite creative solutions.

With laughter and excitement in the air, all loved this idea. It meant they could discover what the public really wanted. It provided a financial solution that wouldn’t cut programs or raise taxes. They quickly articulated the next steps. We were just five minutes over our allotted time, and the enthusiasm was palpable. Collectively letting go, engaging our curiosity, and using reflection to create shared meaning and action was worth it.

As DeAnna’s story shows, when the way opens for expressing deeply felt differences, coherence is not far behind. Reflection makes space for our uniqueness to shine through, to name what matters to us.

I find reflecting one of the most magical and transformative aspects of engaging emergence. Reflecting sets a high bar. It challenges us, as Dynamic Facilitation teaches, to “take all sides” by valuing every contribution. It makes the rich tapestry of different ways of perceiving available to us, getting past triggers that usually block our hearing.

Tips for Reflecting

Reflection has two meanings. One meaning is to contemplate, to consider, actively seeking coherence. The other meaning is to be a mirror for another. Coherence arises in the process.

Be a mirror. Help others to feel heard. Repeat speakers’ words to them. Describe their actions or expressions. Sense their feelings or deeper essence and tell them what you notice. Do it without judgment, with no strings attached, and without giving them advice.

Let of go the need for immediate answers. Make time to explore the depth and breadth of diverse perspectives without requiring a coherent response. Ideas need room to percolate. Relationships take time to form.

Ask questions that seek convergence. Reflective questions are different from questions that open us to face disturbances. Opening questions help us to discover distinctions by making space for wide-ranging exploration. For example, “What’s possible now?” Reflective questions are useful once explorations are well under way. They focus on understanding coalescing themes and patterns. For example: What are we learning? What themes are surfacing that excite us? What is working well? What gifts have we received from this experience?

Pay attention to the timing. Checking for coherence too soon frustrates us. Waiting too long leads to fragmentation, the shadow of differentiation, in which we feel lost in our separateness. Casually ask a converging question—one that connects the dots. For example, what themes and patterns do you notice? What are we learning? What can we name now that wasn’t possible before? If people aren’t ready, the question is soon forgotten in the flow of interactions.

Reflection helps the wisdom that lives within and among us to emerge. When novelty surfaces that contains a bit of us all, yet is unique, we are at a special moment. We are ready to name something into being.

Name: Make Meaning

How do we call forth what is ripening?

Just as opening is a moment of letting go, naming is its counterpart, a moment of coming together. Difference coalesces, forming a novel whole. Naming involves a leap of insight, utterly unexpected and yet long awaited. At last, the finale of our midwifing emergence is at hand when we witness the birth of something new.

Our attention can shape what emerges. Giving something a name helps us to realize its potential. As such, naming something into being is a sacred act. When some scrappy British colonies named themselves the United States of America, a new form of governance was born that rippled throughout the world. Such is the power of names. They bring coherence to life.

Naming can seem like magic. Something unexpected suddenly appears. In practice, it is the culmination of all we have been doing. We inquired appreciatively into something that mattered to us, opened to explore what had heart and meaning, reflected on what ripened. Now we breathe life into our work with a word, a phrase, a name that distills meaning. With a name, a story can be told.

Years ago, I was on the faculty of a women’s leadership program. The women had an assignment to do a service project together. They were given no more guidance. Their selection process and the nature of the project were up to them. At the time, I was living with a question of how collective decisions are made. Watching this group do its work taught me about naming something into being.

Over several weeks, the women identified possible selection criteria for their service project. They researched and shared ideas. And then they got stuck. As they contemplated their options, they were polite with each other, no one wanting to hurt anyone’s feelings.

After several weeks of little action and the clock ticking, someone had enough. She took a stand and made a clear, authentic statement about the project she wanted them to do and why. Once she spoke, another stepped in, speaking her truth. And another. The group listened to each other’s heartfelt expressions. As they reflected on their exchange, their decision was clear. Only one project had characteristics that met some need that each participant had expressed. Out of passionate individual expression, collective commitment surfaced, and a clear purpose was named.

Later, I spoke with the woman who had jumped in first to learn what had prompted her action. She told me that it had been an important moment of letting go. She decided that making a meaningful choice was more important to her than maintaining her image. So she took a risk. That risk opened the way to authentic explorations of needs and longings. It surfaced differences among the women that helped them to coalesce around what really mattered. That moment of naming not only moved them to action, but also brought them closer together as a team.

As this story shows, naming is both an end and a beginning. The women’s search for a project came to a close with their newly discovered clarity. That clarity energized them for the next step of their journey: doing the service project. It also equipped them with deeper, more authentic relationships for the work ahead.

When something novel is named, we are transformed in some way. We may have more faith in ourselves or more compassion for others. We are likely to be more resilient, more tolerant of the unknown. We become a living part of a larger whole, which is a feeling difficult to forget and almost impossible to describe. Having experienced the magic, we may seek it again. If this sounds a bit mystical, try it. With repetition, it may become familiar, something that we have faith will happen routinely. Yet even as our confidence grows, we are unlikely to take it for granted.

Tips for Naming

Emergence culminates in naming. It is the moment when novelty arises.

Call “it” forth. Ask what wants to emerge. Then let go. It may not come. Yet I am amazed how often someone speaks unexpected wisdom that has everyone nodding yes.

Sense that ring of truth. Listen for that moment of surprise and elation, when the diverse people of a system say yes to what arises. Amplify it. Celebrate it when it happens.

If you feel as if you’re working too hard, take a break. Naming can’t be forced. If you keep working it, sometimes names become more elusive. If there’s time, sleep on it. Social psychology offers a body of evidence showing that a night’s sleep supports our ability to sort through complexity. In what is called the Zeigarnik effect, we continue processing uncompleted or interrupted tasks.2 Our unconscious helps new patterns to form that are too tough for our analytic mind. We have all experienced the effect of “sleeping on something” and having it come into greater clarity in the morning.

Have faith. Names arise in their own time. Though analysis may contribute information to the mix, ultimately, naming novelty into being is a complex, nonlinear act. Names arise spontaneously when conditions are ripe.

The magic of naming creates a challenge. How do we share the experience? What can move those who weren’t present?

Harvest: Share Stories

Once meaning is named, how does it spread?

Stories help us to transition. They support us in making sense of what is ending and what is beginning. The arts—music, dance, poetry, film, painting, sculpture, theater, and so on—are powerful carriers of story. They assist in spreading meaning. For example, with rare exceptions, every social movement has songs. During the civil rights movement, the song “We Shall Overcome” instilled commitment to keep going even in the darkest times. Names like industrial revolution, information age, women’s movement, each speak volumes about these accumulated moments in time. They are a shorthand that tells a story.

How we tell stories matters. Is the glass half empty or half full? Is the dying of newspapers a disaster for democracy or an opportunity for some new and better possibility? Since great stories have dynamic tension, it is likely both.

Harvesting stories helps us to share meaning. It carries the seeds of emergence beyond those who were part of a pivotal experience. Given the magnitude of the challenges we face, how can we possibly share meaning on a scale and at a speed that can make a difference?

My colleague Christine Whitney Sanchez faced this question on a national scale, working with Girl Scouts of the USA. Using a variety of harvesting modes, a transforming story of Girl Scouting was revealed, touching three million girls and one million adult volunteers.

From the beginning, the design team for the 2008 Girl Scout National Convention wanted girls to lead the way. Our vision was bold: Design a process that invited members to use their voices, have conversations that mattered, and self-organize to create the future of the Girl Scout Movement. Ten thousand Girl Scouts from around the world participated in the process.

As a lifelong Girl Scout, I was thrilled to head up a consulting team for the StoryWeaving Initiative. Powered by the passions of hundreds of volunteers, collective wisdom and a larger story of Girl Scouting emerged over the four days of the convention.

The team wove together conversation, story, and the arts using Appreciative Inquiry, Digital StoryWeaving, StoryLooms, Open Space Technology, and World Café to create a multimodal experience. While the specific methods weren’t central, their spirit, principles, and practices made all the difference. They provided heart, creativity, and order to deal with the inevitable chaos resulting from this kind of process.

On opening night, members used appreciative questions, printed on “Keepsake Cards,” to converse with new and old friends: “What brought you to this moment?” “Who has helped you to become a leader in this movement?” “What leadership lesson do you have to share?” A “texting poll”—messages entered by phone texting—captured the themes that the members heard in each other’s stories. Real-time results scrolled onto the JumboTrons—big screens in the convention hall.

Fourteen- to 18-year-old girls, armed with Flip video cameras, became Digital StoryWeavers. They captured and produced leadership stories throughout the convention. The production room was abuzz from dawn to dusk, as digital interviews were woven into stories that later premiered on the JumboTrons. Digital StoryWeaving girls authored the larger story of girl power and distributed leadership emerging in the Girl Scout movement.

For those who were more tactile, StoryLooms were set up throughout the convention center. Members wove personal stories into the larger story. Girl Scouts of all ages brought fibers, yarns, strips of old camp T-shirts, weeds, leaves, bark, feathers, and almost anything else from nature to place within the fabric of the StoryLoom. While sharing their leadership stories, they created gifts of friendship and, as a result, a common call to action for the community of Girl Scouting.

Digital StoryWeavers captured the action during the Open Space on successful council membership practices. Self-organized conversations helped members to identify ways to bring the newly revitalized program to even more girls and to promote and expand the reach of Girl Scouting. The 242-page Book of Proceedings is available online.3

A Leadership Café, using the World Café process, surfaced ideas and wishes regarding Girl Scout leadership. A film crew captured the energy of this spontaneous conversation among hundreds of convention-goers. Two short videos on the essence of the World Café process are now available online.4

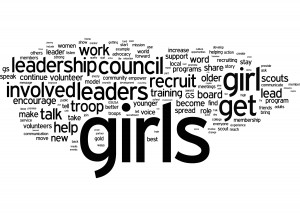

On the final morning of the convention, participants met in their geographic councils to discuss top priorities for the Girl Scout Movement and to identify their own commitments. Results were texted and bounced onto the big screens. Within 24 hours, a member of the StoryWeaving team had posted a word cloud—a visual depiction of the frequency of use of words—on the StoryWeaving site.

Word Cloud of Commitments5

Bushels of collective wisdom were harvested at the convention.6 With support from national staff and local volunteers, Girl Scout troops and local councils have brought the spirit of creative conversation home. They are living an emergent story of a Girl Scout Movement alive with girls in the lead that ripples to this day.

As the Girl Scout story shows, a great harvest takes many forms. With a mix of tools, technologies, artists, and formats, not only did convention-goers benefit from the harvest, but they continue to spread the story long after the end of the event.

Tips for Harvesting

Harvesting tells the stories that are ripe, seeding new possibilities in the process.

Invite artists—both declared and the ones within each of us. Art—music, poetry, movement, visual arts—carries meaning. When artists are present or the artists within are invited to participate, they naturally harvest stories.

Make tools available. Anticipate the need. Have supplies on hand: paper, markers, recorders, cameras—whatever can serve the harvest.

Use many modes. Different people absorb meaning through different means. For many of us, the most effective stories are multimodal. Use text, images, movies, audio, and more.

Share the essential stories. What meaning do we wish to share? What happened? How did it happen? Why does it matter?

Think about whom we wish to reach and how best to do so. A combination of advance thought and ideas that surface in the moment clarify who can benefit from the stories and the forms that work to tell them.

Harvesting makes meaning of what happened and inspires us to engage in what’s to come. It provides energy for doing it again . . . and again.

Back to the Table of Contents